Academic Affairs

Career Access in the Classroom

How to Help Students Recognize the Career Competencies They Build with Their Coursework and Close the “Articulation Gap” The Skills […]

Solutions

Helping higher education create transformational change across campus.

See AllFor Universities

Admissions & Enrollment

Maximize enrollment by increasing yield & reducing melt

Experiential Learning

Scale High-Impact Practices for student success

PathwayU

Redefine how students pick majors & careers with PathwayU

Student Success

Increase retention & persistence to graduation

Career Services

Improve career readiness & career navigation

Industry Partners

Connect universities & corporations for project-based learning

Alumni & Advancement

Grow alumni engagement & the philanthropy pipeline

Success Stories

Read how schools leverage PeopleGrove in their communities.

See All Stories

University of Kansas

How University of Kansas scales career services to their 375,000 alumni

Michigan State University

How Michigan State ensures academic and career success for students

University of Miami

How the Toppel Career Center joined forces with alumni to provide career guidance to students

Resources

Explore blogs, webinars, whitepapers, and more resources to enhance how students and alumni connect.

See All ResourcesBlog

Read posts about how PeopleGrove meets higher education’s ever-changing needs at every turn.

Events

In-person or online, join PeopleGrove for unmatched experiences, conferences, webinars, and more.

Research Library

A collection of stories, events, research, and best practices to transform learners’ experiences.

Super Mentors Book

The ordinary person’s guide to asking extraordinary people for help.

Innovators Community

Learn from thought leaders and practitioners in both higher education and workforce development.

About

PeopleGrove is made for learners by learners. Everyone here makes it possible for students and alumni to succeed.

Learn MoreCareers

Be a part of the next big thing for learners everywhere and start making an impact. Join us today!

Contact

Want to get in touch? Have a question? We’d love to hear from you. Connect with us.

Academic Affairs

How to Help Students Recognize the Career Competencies They Build with Their Coursework and Close the “Articulation Gap” The Skills […]

Read any thinkpiece or report on the future of work, and you’re bound to come across the ominous moniker “the skill gap.”

(Cue Star Wars’ “Imperial March”)

According to the Brookings Institute, the “term ‘skills gap’ describes a fundamental mismatch between the skills that employers rely upon in their employees, and the skills that job seekers possess.1” And as more and more hiring managers say that skills matter more than degrees,2 closing this gap has become crucial for those in the workforce development space.

However, much of the conversation in the media revolves around the “hard skills” that employers seek for the majority of today’s in-demand jobs. So much so that many of the solutions presented simply eliminate higher education from the conversation, assuming that training programs or even employers themselves can accomplish the job more effectively and efficiently.

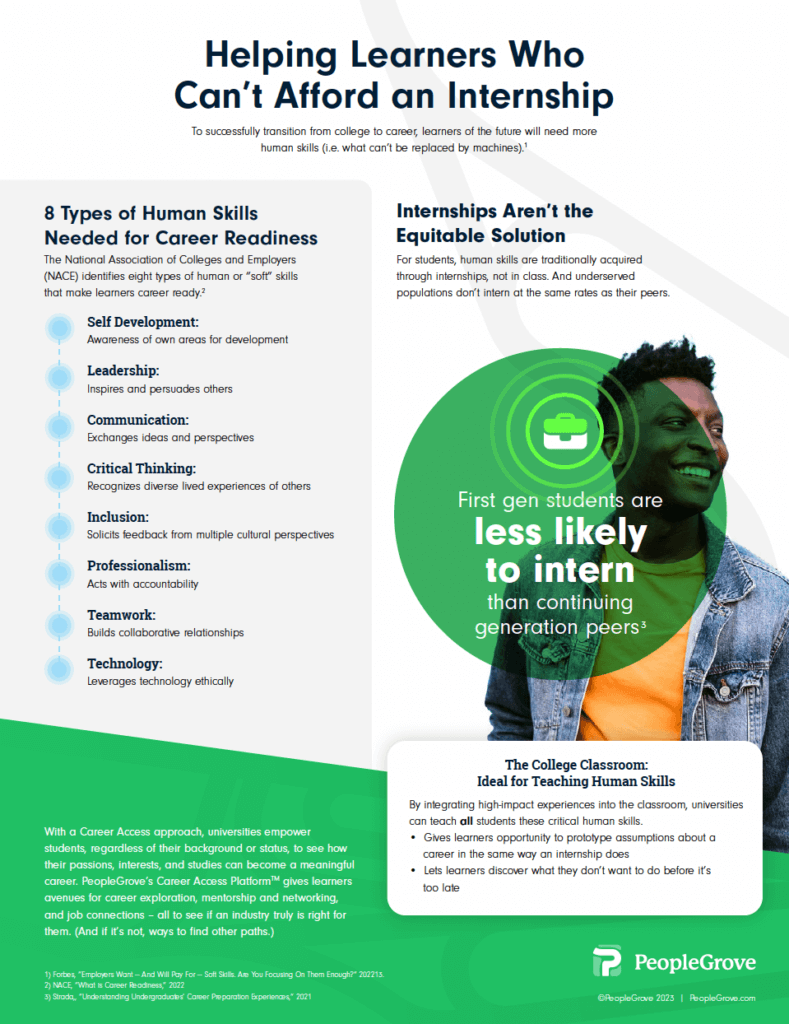

What is often overlooked are the “soft skills.” If you look through the competencies and skills identified by organizations like the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE),3 the World Economic Forum,4 or even McKinsey5 you’ll find more of these soft skills than you will hard skills. And as technology improves and as “jobs are likely to be lost to machines, we should embrace the opportunity to spend more time tuning and developing skills and abilities that make us human.6”

They’re not soft skills — they are human skills.

From a workforce development perspective (and yes, higher education is in the business of workforce development), this presents colleges and universities with a tremendous opportunity. As we wrote in Career Access: Higher Education’s New Core Differentiator, institutions need to find a way to help them stand out in a suddenly very crowded learning ecosystem. Learners now have other faster, cheaper options that they can leverage to help them get a good job. But so many of those other options only focus on the hard skills.

Higher education has the opportunity to demonstrate its value by ensuring that learners build these human competencies in their coursework. This is at the foundation of a Career Access approach. Luckily, this is already happening. And yet learners tell us that’s not as explicit as it needs to be.7

In fact, faculty say the same thing. In a recent article for NACE, Josh Domitrovich, Executive Director of the Center for Career and Professional Development at Pennsylvania Western University (PennWest) described listening sessions he hosted with faculty as his institution went through a reorganization of career education following a merger:

Faculty unanimously agreed that the deficiency they would most like to see improved in their current students and recent graduates was their soft skills—the career readiness competencies. Further investigation and clarification of this showed that they were not referring to a skills gap—it was an “articulation gap.” The issue faculty faced was that students were unable to connect how assignments and experiences supported their skill development, which led to poor articulation of the skill.8

Students were building the competencies. They just can’t explain how.

It’s easy to see how, say, a business school class that requires group projects helps students build competencies like teamwork or professionalism. So let’s take a more extreme example in a history class on Julius Caesar. Typically, these classes are your classic reading/writing/lecturing type of courses. Read a portion of the Gallic Wars, write an answer to a prompt, and then come to class to hear the professor’s take.

Certainly, it’s not a stretch to say that students can learn something about the competency of leadership from this type of class. Would it be such a stretch to ask professors to craft their writing prompts or class discussions around how the lessons of Caesar’s leadership apply to the boardroom?

While those simple changes help make these connections more explicit, hearing it is different than experiencing it. We need to ensure that students have the opportunity to see how these competencies actually make a difference in the working world.9 High-impact experiences, such as short term projects in a work setting, paired with social capital building activities like networking allow students to see their classroom discussions in action. Imagine a student being able to talk with an alum who took that same Julius Caesar class while observing how leadership decisions are made in the context of a real-world project. The classroom to career connection would certainly be far stronger.

Taking a Career Access approach, colleges and universities have the opportunity to differentiate themselves from other learning and certification options. And these human skills play a big role in where that differentiation lies. As Seth Bodnar, President of the University of Montana wrote in Inside Higher Ed, “Future leaders need the tangible skills to do their jobs well immediately upon graduation, but also the foundational cognitive capacities and broad-based knowledge to navigate uncertainty and cope with ambiguity throughout their careers.”10 The human competencies that learners build in higher education don’t just set them up for an in-demand job today, it helps them navigate the twists and turns of a lifelong career journey.

Career Access is the principle that every individual, regardless of their background or status, has the ability to fully understand how their passions, interests, and studies can become a meaningful career. Then, with newfound confidence and vital resources, they can build the competencies necessary to achieve and succeed in that career.

But if we are not intentionally, strategically, or explicitly showing students how their classes translate into workplace success, we are not fulfilling that promise. Career Access depends on students knowing that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. And by making learner-first changes in partnership with colleagues across campus, we can ensure that we are reaching every student and setting them up for success.

Keep reading about this promising new concept in Career Access: Higher Education’s New Core Differentiator.

Browse more research and insights.

Career Services

For nontraditional students pursuing higher education while balancing work, family, or both, support can be key to student success. University […]

4 min read

Alumni & Advancement

In 2022, PeopleGrove released the first-of-its-kind impact report. Its goal was to understand how student-alumni engagement communities – which PeopleGrove […]

4 min read

Career Services

How Science and Deep Insight are Shaping the Future of Career Services The Promise of Informed Choices Imagine knowing […]

3 min read